CLAUS LEGGEWIE - Reappraising the politics of ’68

Retrospectives of 1968

tend to dismiss its socialism and instead to see identity politics as its

primary legacy. Rightly so? Leggewie asks how far the New Left achieved

its political goals and whether identity politics were necessarily incompatible

with its anti-capitalist & social-revolutionary agenda.

Let it be emphasized:

no social scenario, however desolate, justifies abuse of or discrimination

against minorities. Nor, however, does the mere affirmation of cultural

diversity, together with politically correct language, remedy deleterious

social and employment conditions, which are again affecting women and

minorities disproportionately. One has to keep an eye on both things – there

are no major and minor contradictions, as Marxism-Leninism once saw it. Sexism

and racism are one side of the story, the voters who defect to the far-Right

because for decades they have not felt represented by established parties are the

other... There can be no

alternative between collective identity and class, between artistic and social

critique, between equality and difference, between universalism and

particularism. An ambitious politico-social movement must consider both strands

in combination. Capitalism is more than an economic subsystem. As Karl Polanyi

argued some seventy years ago, it is a mode of socialization that posits

difference as inevitable. Today, not for the first time, it blames inequality

and exploitation on those whom they affect.

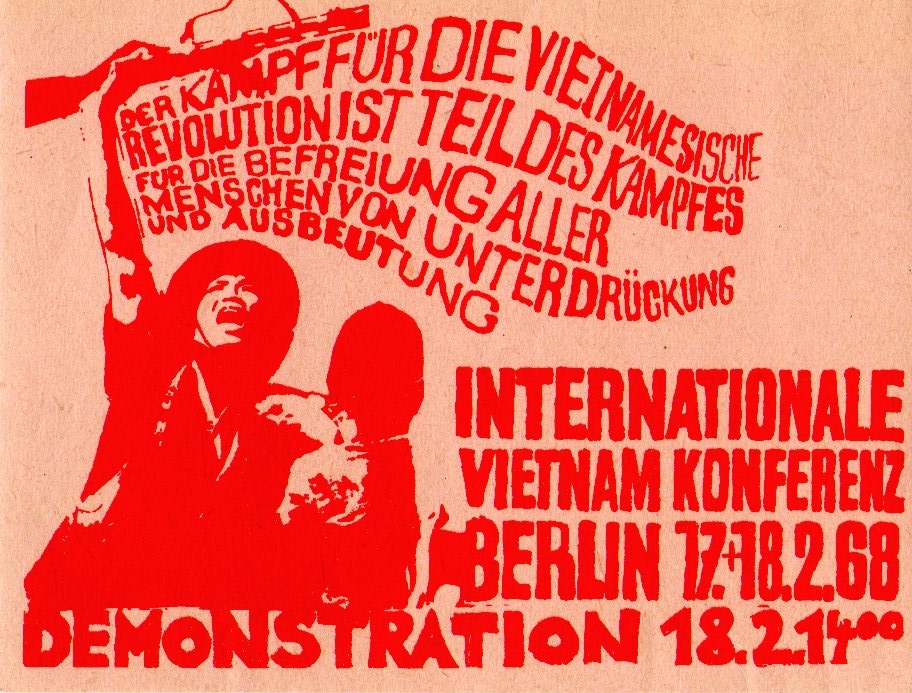

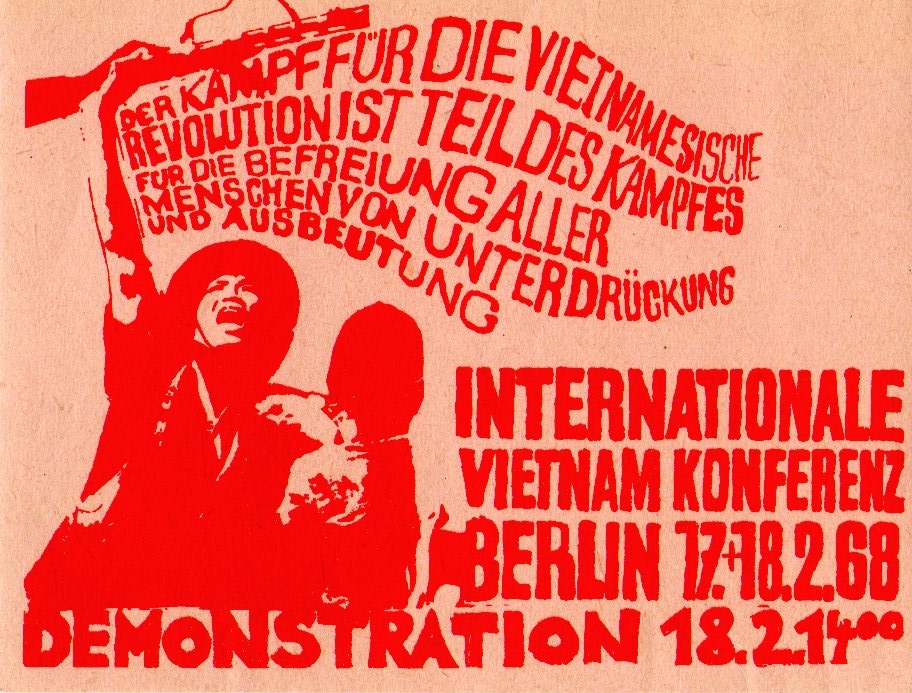

February 1968. Radical

leftists from all over the world are in West Berlin to attend the International

Vietnam Congress. The main auditorium of the Technical University is packed to

the rafters. A banner has been draped over the edge of the viewing balcony

demanding the ‘liberation of all people from oppression and exploitation’.

Hanging next to it is the resplendent image of Ho Chi Minh. The Tet offensive

has just demonstrated the vulnerability of the US military in Southeast Asia

and an American defeat has become a real possibility.

Among those attending the

conference is the little known French anarchist, Daniel Cohn-Bendit. The main

attraction, however, is Rudi Dutschke, the charismatic leader of the Socialist

German Student League (SDS). Dutschke delivers his speeches with deep pathos

and is fond of citing Marx’s mantra about ‘the categorical imperative to

overthrow all relations in which man is a debased, enslaved, forsaken,

despicable being’. ‘Comrades! We don’t have much time!’ he exclaims on the

second day. ‘Every day, we too are being crushed in Vietnam, and not just

figuratively speaking.’ At this very moment, Dutschke is vacillating between

giving up the fight or becoming a ‘real’ urban guerrilla. Shortly afterwards,

he is vilified for appearing on the cover of the magazine Capital for

a thousand deutschmarks. Then, in April, he is shot three times by a neo-Nazi

on the Kurfürstendamm.

What does this

breathless, desperate political existentialism have to do with this year’s

polished retrospectives of 1968? How did the socialist impetus for the Vietnam

Congress, with its identification with the workers’ movement, relate to other

arenas of revolt? To the university, for example – the home of the students and

the starting point of the revolts, which was supposed to be transformed into a

‘critical university’? To the global pop-cultural movement, the subculture that

drove the youth revolt? Or to the women’s movement, which put sexual equality

on the agenda once and for all. ‘We students’, ‘we young people’, ‘we women’ –

how did these collective identity-markers relate to the ’68ers’ committed

anti-capitalism and utopian socialism? What remained of this socialist impetus

in later decades and what remains relevant today?

The instigators of the

revolt understood themselves as social revolutionaries. They wanted to overcome

‘late capitalism’, which they believed could not be reformed, and build a free

society. In part, this emulated ‘real socialism’ and in part was clearly at

odds with it. As to what the adjective ‘socialist’ might mean, they had no

concrete idea. As with many of their ideological precursors, not least Marx,

there was little relation between the ferocity of the critique and the clarity

of the alternative. The socialist ’68ers were primarily anti-capitalists,

counting on a dynamic emerging from the class struggle; specific questions

about how the ‘new society’ was to be organized were saved for later... read more: