Adam Lusher - Story of the last survivor of the last slave ship to travel from Africa to US is published after 87 years

When Hurston hailed him by his African name, it brought tears of joy to his eyes. When she told him she wanted to hear his life story, she wrote, “His head was bowed for a time. Then he lifted his wet face: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’” At the time, Hurston was becoming part of the ‘Harlem Renaissance’, an artistic and political movement that took pride, rather than shame, in black America’s African origins... She knew who Cudjo was: “The only man on Earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.”

The descendant of the

last survivor of the last slave

ship to take captives from Africa to

America has spoken of his pride at seeing his

great-great-grandfather’s story finally being published – 87 years after it was

first written. Garry Lumbers

told The Independent he wouldn’t just buy the book

Barracoon for himself. He would buy copies

for all his 22 grandchildren, and study it with them, to play his part in

ensuring that never again would the world neglect the story of his great

ancestor: born in Africa as Kossula, died in America in 1935 as Cudjo Lewis.

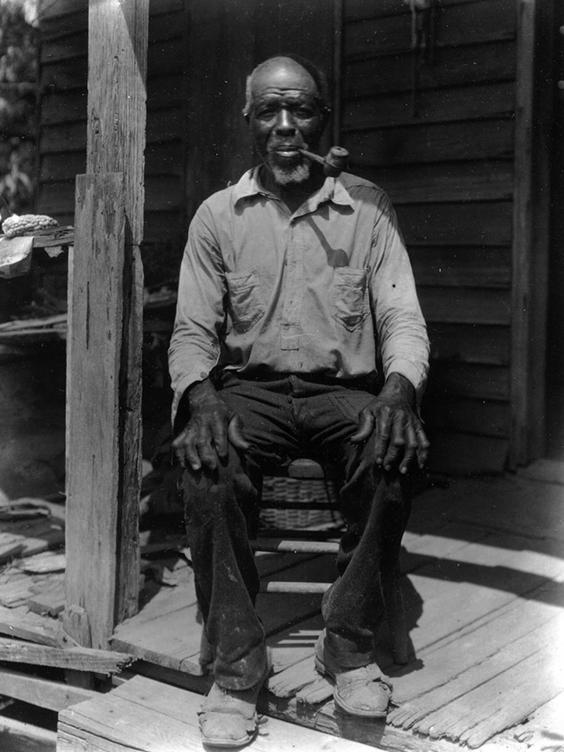

Cudjo Lewis - Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and

Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

“I am delighted,” said

Mr Lumbers. “I am so proud, so grateful that his story is is going to be

published and that it won’t ever be forgotten.” Mr Lumbers grew up in

the house that Cudjo built, on the two acres of land that he bought with the

$100 that somehow he scraped together from hard but paid labour after being

freed as a result of the American Civil

War. Throughout his

childhood, Mr Lumbers heard tales told by his grandma, of a warrior in

chains, shipped

to America, it was said, so a rich white man could win a bet that he could

smuggle a consignment of captives 51 years after America had supposedly banned the importation of slaves. He learned too of how

after they were freed, Cudjo and his fellow ex-slaves worked together to build

a new community: Africatown, now known as Plateau, in Mobile,

Alabama.

Cudjo himself had told

snippets of his story to various newspapers and researchers. But it was

only the black writer Zora

Neale Hurston who took the time and trouble to let him tell the full,

book-length story of his life. She did so when Cudjo

was in his 90s, by then the last person alive out of the 116 humans who had

formed the “cargo” of the slave ship Clotilda in 1859. But when Hurston

submitted the story to publishers in 1931, no-one wanted it. Cudjo died four years

later, aged about 94, with his story still not properly told. Though celebrated

today, Hurston died in poverty in 1960, buried aged 69 in a pink

dressing gown and fuzzy slippers in an unmarked grave in a segregated Florida

cemetery.

Her Barracoon manuscript

- its title taken from the name for the African holding pens for captives

awaiting sale and shipment into slavery - languished in an archive at her alma

mater Howard University. It would probably have

stayed there too, but for the fact that quite recently her literary trust

acquired new agents. Were there, the new

agents asked, any unpublished works? Now the

publisher Harper Collins is

saying that when Barracoonfinally hits book shops on both sides of

the Atlantic on Tuesday May 8, it will be “a major literary event.” Some see it as a

political event too.

Valerie Boyd, the

author of the acclaimed Hurston biography Wrapped

in Rainbows, has been quoted as saying “We’ve got an open bigot in

the White House. A book like Barracoon says,

‘Yeah, black

lives matter. They’ve always mattered.’” Mr Lumbers simply

says: “Let’s finally publish the book and let the world know what

happened.” For him Barracoon is

a testament to his forefather, to all those who travelled in the hold of the

Clotilda and who used their freedom – once they got it - to forge a new life

for themselves. “It is time,” he says,

“For America to know who these people were.”

That certainly seems

to have been what Cudjo wanted.

When Hurston hailed

him by his African name, it brought tears of joy to his eyes. When she told him she

wanted to hear his life story, she wrote, “His head was bowed for a time. Then

he lifted his wet face: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want

tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and

callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’” At the time, Hurston

was becoming part of the ‘Harlem

Renaissance’, an artistic and political movement that took pride,

rather than shame, in black America’s African origins.

She knew who Cudjo

was: “The only man on Earth who has in his heart the memory of his African

home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery;

and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.” Hurston knew how

rarely the voice of the African-born slave had been heard. “All these words from

the seller,” she wrote, “But not one word from the sold. The kings and captains

whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo. The thoughts of the

“black ivory,” the “coin of Africa,” had no market value.

“Africa’s ambassadors

to the New World have come and worked and died, and left their spoor, but no

recorded thought.” And so she came

from New

York to a Southern home with a garden gate that was locked using “an

ingenious wooden peg of African invention”, to talk to an old man eating his

breakfast “with his hands, in the fashion of his fatherland”. When the old man

talked over the peaches and Virginia ham she brought him, she listened. And when he refused to

talk, she helped him clean the church where he was sexton, or drove him into

Mobile to buy some turnip seed. When she couldn’t find

an Alabama hotel that would rent her a room, Hurston slept in the Chevrolet

coupe she called "Sassy Susie", with a pistol for protection.

And finally, she wrote

Cudjo’s story, in his words, in his dialect.

It was a story of epic

proportions, told by an old man in a foreign land, infused with his longing for

Africa. It begins in a modest

but proud home in Benin, with

a young man training to be a warrior: “I grow tall and big. I kin run in de

bush all day and not be tired”. He never thinks about

what might be happening across an ocean he has never even seen. According to some

accounts, Captain Tim Meaher, of Mobile, Alabama, has bet a northern businessman $100,000 he can smuggle a

“cargo”, despite America having enforced a ban on slave importation (as opposed

to ownership) since 1808.

Meaher commissions the

fast schooner Clotilda. Skipper Bill Foster sets sail with instructions

to buy slaves at a rate of $50-$60 each.

And Kossula’s village

is raided by warriors loyal to the Dahomey king, the head of a dynasty which

has grown rich by fulfilling the white man’s insatiable demand for

slaves. For Kossula, now in his late teens, there is no escape. “I call my mama name.

I beg de men to let me go findee my folks. De soldiers say dey got no ears for

cryin’.” As he is led away, he

sees in the hands of the Dahomey warriors the severed heads of his fellow

villagers. He watches them smoke the heads so they don’t spoil in the

heat: “We got to set dere and see de heads of our people smokin’ on de stick.”

After three weeks in

the barracoon, the buyer arrives: “De white man lookee and lookee. He lookee

hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose.” The slaves are

stripped of their clothing, possibly to improve hygiene in the stifling

conditions of the Clotilda’s hold, although none of that is explained to

Kossula: “I so shame! We come in de ’Merica soil naked and de people say

we naked savage.” Then comes 70 days

of thirst

and sour water, on a terrifying sea that “growl lak de thousand

beastes in de bush”.

But since none of the

slaves die or fall sick, Cudjo considers Captain Bill Foster “a good man”. He counts himself

lucky to be bought by Jim Meaher, who was less keen on seeing his slaves beaten

than his brother Tim. But there were

beatings. “De overseer, de whip

stickee in his belt. He cutee you wid de whip if you ain’run fast ’nough to

please him. If you doan git a big load, he hitee you too.”

And then on April 12,

1865, “De Yankee soldiers dey come down and eatee de mulberries off de

trees. Dey say ‘You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo’. “We so glad we makee

de drum and beat it lak in de Affica soil.”

Cudjo even asks Tim

Meaher to give the ex-slaves land, since he had taken them away from their land

in Africa: “Cap’n jump on his

feet and say, ‘Fool do you think I goin’ give you property on top of property?

I doan owe dem nothin.” Meaher never paid for

his slave smuggling. No-one insisted on payment of the court fines

imposed on him, his brother and Captain Foster. And when by working in

the saw and powder mills, and on the railroad, and by selling vegetables, the

ex-slaves earned enough money between them to buy land from the Meahers, “Dey

doan take off one five cent from de price”.

They bought the land

from their former masters and built Africatown.

Garry Lumbers beside

the grave of his great-great grandfather Cudjo Lewis (Garry

Lumbers/ Frederick Lumbers). Cudjoe married

Abila. They gave each of their six children an African name “because we

not furgit our home”, and an American name that wouldn’t “be too crooked to

call.”

Yah-Jimmy, Aleck, was

Mr Lumbers’ great-grandfather. They faced prejudice,

from black as well as white Americans. Cudjo’s sons were called ‘ignorant

savages’ and “kin to monkey.”

They faced tragedy

too, the loss of all Cudjo’s children but Aleck through illness or accident.

His youngest son, also

called Cudjo, was shot dead by a police officer. The officer himself

was black, but the story might sound wearyingly familiar to the modern Black Lives

Matter movement: “He make out he skeered my boy goin’ shoot him and

shootee my boy …. My po’ Affican boy dat doan never see Afficky soil.” And yet Cudjo became a

respected leader in his community, the sexton of the church they built, the

“Uncle Cudjo”, to whom people came seeking wisdom, asking for “a parable”.

Once Hurston had written

up his story, it resonated with humanity as well as drama.

“At last,” she wrote

in a letter of April 18 1931, “Barracoon is ready.” And no publisher

wanted it.

Did the “thoughts of

the ‘black ivory’, the ‘coin of Africa’”, still have no market value? Various reasons have

been suggested for the rejection, one of them being Hurston’s insistence on

telling Cudjo’s story in Cudjo’s dialect. The Viking Press did

contact her, but only to ask for a rewrite “in language rather than

dialect”. She refused.

Perhaps because of her anthropological training, perhaps because she was ahead

of her time, Hurston saw Cudjo’s dialect as a vital and authenticating feature

of his story.

In some publishers’

minds there may have been concerns similar to those later expressed in 1937

when Hurston’s most celebrated novel, Their

Eyes Were Watching God, came out. Some black critics eviscerated

it for its use of dialect. Hurston’s fellow

Harlem writer Richard Wright wrote, witheringly: “Miss Hurston voluntarily continues

in her novel the tradition which was forced upon the Negro …

the minstrel technique that makes the "white folks" laugh … [which]

evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the ‘superior’ race.” There have also been

suggestions that Cudjo’s story was problematic because of the way it

highlighted African involvement in slave taking.

It in no way altered

the fact that voracious European and American demand for slaves had created

incentives for captive taking beyond anything ever seen before in Africa. Nor did it change the

fact that the new market for slaves turned them from the prized human

possessions they had historically been into mere beasts of burden, whose

mistreatment was justified by a racist literature demeaning them as incapable

of a white person’s ‘feelings’. But it potentially sat

uneasily with anyone seeking to promote a Harlem Renaissance that took pride in

black America’s roots.

Hurston herself later

wrote that what Cudjo told her “Did away with the folklore I had been brought

up on – that the white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at

the Africans and lured them aboard ship and sailed away.” Whatever the reason,

she never saw Barracoon published.

“There is no agony,”

Hurston once wrote, “like bearing an untold story inside you.” Despite becoming briefly famous due to her

other work, the largest royalty she ever received was

$943.75. By the time she died all her works that had been published

were out of print.

She had suffered the

humiliation of being spotted, in 1950, working as a low-wage servant in a Miami

suburb, with the resulting, vicious headline: “Famous author working as maid

for white folks down in Dixie". After she died in a

Florida welfare home, her neighbours had to club together to pay for a cheap

funeral. Her name was misspelt on her birth certificate. It was only after her

death that her true worth was recognised.

Alice Walker, the

Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The

Color Purple, who has written the foreword for the newly

published Barracoon, found her grave and marked it

properly. The headstone read: "Zora Neale Hurston, A Genius of the

South.” Cudjo too has a

physical monument, to go with his soon-to-be published literary one. It is his towering

tombstone in the graveyard of the church where he was sexton, in the heart of

Africatown, the place he helped build. On every return visit

to Plateau, the first thing Mr Lumbers does is pay his respects there.

For him, Cudjo and

those who formed the “cargo” of the Clotilda have a place in the history of a

struggle that included famous figures like Martin Luther

King, and other, less famous people, like his aunt Martha, the

great-granddaughter of a slave: “She went to a

predominantly white college and got herself a Masters, became a teacher.

Can you imagine how hard that was for her?” But, says Mr Lumbers,

Cudjo and his companions also deserve their place in the story of the American dream.

When asked the moral

of his great-great grandfather’s story, he answers without hesitation: “You

never give up. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” Cudjo arrived in

America without even the shirt on his back. Yet he and his fellow

ex-slaves worked together to buy land, to build themselves a church, a school,

a community. “Cudjo was a great

man,” says Mr Lumbers. “He started from nothing, from dirt. He

rolled his sleeves up, pulled his pants up and got his hands dirty.” Mr Lumbers is 61 now,

living in Pennsylvania and still working – somewhat ironically, this descendant

of the last survivor of the last American slave ship specialises in the

logistics of shipping cargo. But he is looking forward to retirement.

And like Cudjo did, he

yearns to return home – although, of course, for Mr Lumbers ‘home’ is Plateau,

Africatown, the substitute community his forbear created when he realised that

return to the real Africa was impossible. Plateau, says Mr

Lumbers, has fallen on hard times of late. The jobs have dried up. “They forgot about

this place,” says Mr Lumbers. “Plateau became somewhere that trucks pass

through, on their way to the Interstate 65.” 'I imagine Cudjo Lewis

would be grinning on that old cane pipe and saying ‘So, they’re finally going

to do the right thing …’

He longs to be able to

help restore Plateau to what it should be – a thriving community, one that

attracts tour buses that stay, not trucks that leave, a proud embodiment of his

family, and America’s heritage. He hopes the

publication of Barracoon will be a spur in that direction. And he knows that his

great-great grandfather would be proud to see his words published at last. “He can rest easier

now,” says Mr Lumbers. “I imagine Cudjo Lewis would be grinning on that

old cane pipe of his and saying ‘So, they’re finally going to do the right

thing …’ “It is a story that

needs to be told.”