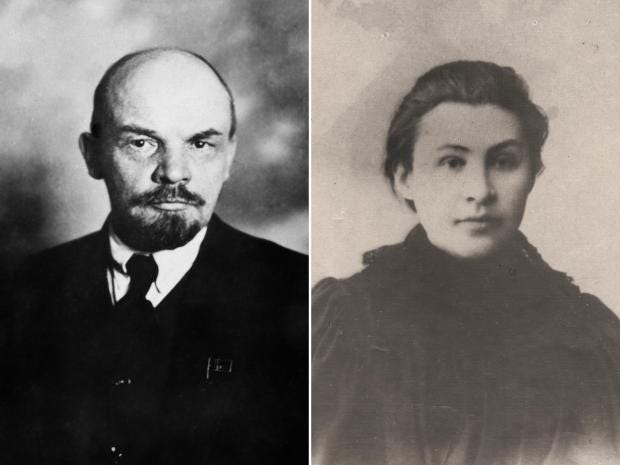

Apollinariya Yakubova: The face of the woman Vladimir Lenin loved most is revealed

She was described admiringly by Vladimir Lenin’s wife as the

“primeval force of the Black Earth”, a revolutionary firebrand with sparkling

brown eyes whose natural aroma was of “fresh meadow grasses”. It is no wonder then that the search for an image of

Apollinariya Yakubova, considered by some to be the Communist leader’s true

love, has captured the imagination of generations of historians. Her

complex relationship with Lenin and their explosive disputes over party policy,

while both were living in London, are well documented

The photograph of Apollinariya Yakubova discovered by Dr Robert Henderson

Until now, a photograph of Yakubova has proved elusive. But

on 1 May, the Camden New Journal revealed her face for the first time after a

researcher dug deep into forgotten vaults in Moscow. Dr Robert Henderson, a Russian history expert at Queen Mary

University, made an unexpected discovery in the State Archive of the Russian

Federation earlier this month while researching the life of another

revolutionary.

Concealed in a string-tied bundle of papers was a black and

white photo taken while Yakubova was in a Siberian camp, where she was

incarcerated for political activity before travelling to Britain. “She is quite a beauty,” says Dr Henderson. “Yakubova

possessed numerous qualities that would attract even the most stony-hearted…”

Academics have long debated whether Lenin ever recovered

from being rejected by Yakubova – or “Lirochka” as he called her – after she

spurned his marriage proposal. Their intimate letters have been scrutinised,

and much attention paid to the scorn that was later to be heaped on her by

Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, who had been one of her closest allies.

The love triangle was played out a stone’s throw from the

British Museum reading rooms that attracted many Russian exiles early last

century, when Yakubova, then aged 27, lived on Regent Square. Records show that

after being imprisoned in the Siberian camp for political activity, she escaped

and travelled 7,000 miles to London, where she met up with Lenin and Krupskaya,

and became central figure in the party.

Yakubova is celebrated for orchestrating politically charged

debates in the East End, where the finer details of Communist doctrine were

contested by poor, working-class Russian émigrés. Her role as a key member of

the group running Lecturing Society debates in Whitechapel came to an

“acrimonious end” after ideological differences split the tight-knit group.

While living in Russia she had clashed over political theory

with Lenin, who lived intermittently in London between 1902 and 1911. Yakubova

preferred a brand of “organised democracy” where working people were more

involved in the party compared with Lenin’s favoured “centralism”, where a

small group of professional revolutionaries called the shots.

In Dr Henderson’s essay, approved for publication by the

peer-reviewed Revolutionary Russia journal later this year, he writes: “In the

heat of the argument, Lenin accused her of anarchism, which indictment affected

her so strongly that she felt physically ill.”

But the tempestuous relationship would later sour as

divisions grew, with Krupskaya penning “bitter missives” about her former

comrade, saying: “To me Lirochka is now an X. To tell the truth, I cannot

reconcile myself to her marriage [to Party organiser Konstantin Takhtarev].”

What became of Yakubova in Russia is not known. The

last-known trace of Lenin’s lost love came from Takhtarev, who in 1924

described Yakubova as “my selfless friend who magnanimously sacrificed her life

for the cause of the emancipation of labour”. She is believed to have died

between 1913 and 1917. Dr Henderson said: “Like so many others whose names have

been erased from the history of the Russian revolutionary movement, Yakubova

deserves some belated recognition.”

See also

Book review: new biography of Stalin Reviewed by Donald Rayfield